This article was originally published as a guest column in Outsourced Pharma.

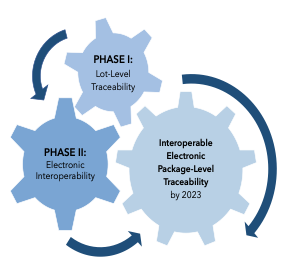

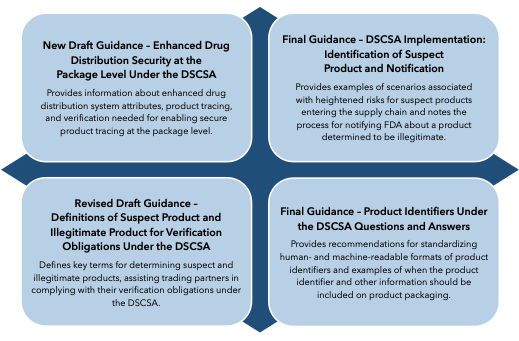

This month kicks off the final year of a decade-long process to enhance overall security of the U.S. prescription drug supply chain under the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA).1 To foster enhanced security, the DSCSA outlines steps to build a fully interoperable, electronic system for tracking and tracing drug products at the package level. In so doing, the law, enacted in 2013, has called upon the FDA and the full spectrum of supply chain trading partners — from manufacturers to repackagers to distributors to dispensers — to align on key implementation requirements by Nov. 27, 2023. The FDA, for its part, has been phasing in pertinent guidance documents to support DSCSA implementation.2 (For a summary of 2021’s guidances, see “Navigating DSCSA Implementation: Key Requirements & 4 New FDA Guidances.”)

Now, ongoing questions of whole industry readiness remain a mixed bag as the law’s November 2023 deadline comes into sight, although some progress has been observed.3 This article looks at this year’s DSCSA implementation efforts, before examining where implementation currently stands and what gaps and challenges remain.

2022 DSCSA Implementation Advances

Despite 2021 efforts, a lack of clarity on trading partner and product tracing standards meant that implementation hesitancy persisted.4 While 2022 brought resolution to some outstanding questions, others remain open.

In February 2022, the agency issued long-awaited licensing standards for wholesale distributors (WDs) and third-party logistics providers (3PLs).5 The following month saw revised draft guidance on verification systems, which granted trading partners more time to respond to requests for verifying suspect or illegitimate products.6 Then, in July 2022, the FDA issued revised draft guidance on identifying authorized trading partners, as well as revised draft guidance on electronic tracing standards.7

National Licensing Standards for WDs & 3PLs

Early this year, the FDA issued a proposed rule setting forth licensing standards for WDs and 3PLs, as it is mandated to do under the DSCSA.8 Significantly, in guidance describing the impact of the proposed rule on product tracing, the FDA said that section 585(b)(1) of the Federal Food, Drug, & Cosmetic Act (FDCA) preempts state licensing laws that establish stricter standards.9 This means that states may only continue licensing WDs and 3PLs if they match federal requirements, promoting industry-wide uniformity and clarifying expectations among trading partners. Prior to the proposed rule, manufacturers across states had to navigate a patchwork of state licensing regulations to ensure their trading partners were appropriately authorized, burdening compliance with a key DSCSA requirement.

Stakeholder comments made in response to the proposed rule were largely supportive of the FDA’s preemption position, since uniformity of national requirements is consistent with DSCSA principles for enhancing supply chain security.10 Concurring with these comments, the Healthcare Distribution Alliance (HDA) also called for uniformity between licensing standards for WDs and 3PLs, explaining that even “minor differences may distract both the regulated and the regulators from whether the difference is meaningful and intended, mandated by differences in the DSCSA, or simply a drafting artifact.”11

Additionally, revised draft guidance issued in July 2022, Identifying Trading Partners Under the DSCSA, addresses previously unclear statuses of trading partners involved in product tracing (i.e., private-label distributors, salvagers, and returns processors and reverse logistics providers), along with confusion around certain drug distribution scenarios.12 The revised draft guidance also clarified the licensure status of 3PLs prior to the effective date of the new licensure regulation. Taken together, the new proposed rule and draft guidance helps clarify who exactly trading partners should be engaging with, particularly among interstate trading partners, in fulfilling another key DSCSA requirement.

Electronic Tracing Standards

In July 2022, the FDA also issued revised draft guidance, DSCSA Standards for the Interoperable Exchange of Information for Tracing of Certain Human, Finished, Prescription Drugs, clarifying expectations for complying with electronic standards for tracing products.13 Most significantly, this draft guidance recommends that trading partners use GS1’s Electronic Product Code Information Services (EPCIS) standard when exchanging and maintaining transaction information and transaction statements. GS1 is a widely recognized nonprofit organization that designs and maintains global standards for business communications.14 While the previous iteration of the draft guidance recommended the use of GS1, it also allowed for the use of other methods and standards. This created confusion as to what the agency considered to be adequately harmonized standards and led many trading partners to refrain from adopting any standard before a final recommendation was made clear.

This newer version of the guidance is consistent with the DSCSA requirement that the FDA make standard recommendations that are consistent with those of widely recognized international organizations.15 An August 2021 report from the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA) endorsed GS1 as an appropriately accepted international standard for data exchange as part of global track and trace systems.16 Additionally, GS1’s EPCIS standard had been most supported by industry and was being used as the basis of the interoperable system built to date.17 Thus, the recent, more direct recommendation from the FDA, to use the GS1 standard alone, aligns with industry calls and ICMRA’s endorsement, and will hopefully activate its more fulsome adoption.

One Year Out: Progress Observed, But Challenges Remain

With one year to go before DSCSA requirements for electronic, package-level traceability and verification are enforced, strong evidence suggests that industry readiness may be coming into focus, at least for some trading partners.18 That is according to a recent HDA report detailing results of its annual Serialization Readiness Survey, in which 48 manufacturers and 29 distributors shared their perspectives on current system capabilities. Although many of the survey participants appear to be in good shape for 2023 compliance, the report also showed signs of a supply chain that still demonstrates “uneven readiness” as a whole. Additionally, the FDA and industry remain apart on data management expectations, a key mechanism for ensuring whole system interoperability.19

Manufacturer Readiness

In a sign of progress, the HDA survey found that 75% of manufacturers plan to send all serialized data with shipments by November 2023, with nearly a quarter of manufacturers aiming to do so sooner (i.e., by the end of 2022). Additionally, over 57% of manufacturers are already aggregating data for all their products, up from 45% last year, and another 6% plan to aggregate by the end of 2022. Aggregation of unique product data at the package level must take place before data can be exchanged with other trading partners, so it’s good news that a majority of manufacturers have already taken this initial step, or soon will. Also encouraging is news that most manufacturers (87%) currently use the latest 1.2 version of the FDA recommended EPCIS standard. Nearly all of the remaining participants indicated they use earlier versions of EPCIS, with most planning to transition to the newer version by 2023. Even further, 84% of manufacturers said they don’t have any concern about their ability to support the distributors’ saleable returns verification requirement.

Despite progress, less promising is the 36% of manufacturers that say they won’t begin aggregating data until sometime in 2023, as well as the 2% that are usure when they will be in the position to send serialized data to distributors at all.

Distributor Readiness

Of course, in terms of 2023 interoperability, manufacturers’ ability to send serialized data means little if distributors are unable to receive it. Fortunately, according to the HDA, 62% of distributors reported having current capabilities on this front, with nearly two-thirds of the rest looking to do so by the end of 2022. Interestingly, despite a significant number of manufacturers and distributors anticipating being able to send and receive serialized data by 2023, 46% of distributors said they aren’t receiving any serialized data with transactions, and another 46% said they are receiving serialized data with only 1–5% of transactions.

Additionally, unlike their manufacturer counterparts, more distributors (45%) had concerns with their ability to meet the saleable returns verification requirement, citing challenges such as complete availability of master data, accuracy and completeness of data exchange, and challenges receiving EPCIS files, among others.

Remaining Challenges

Trading Partner Collaboration Challenges

Perhaps more insightful were survey datapoints highlighting the major challenges that manufacturers and distributors still face in terms of meeting their requirements. Per the HDA report, manufacturers cited collaboration with trading partners, governance of the interoperable system, and differences in interpretation of the law as top hurdles for 2023 compliance. Distributors similarly cited collaboration with trading partners as chief among challenges, in addition to technical challenges, establishing standards, and connectivity and related security. Thus, in its final year of implementation, collaboration among trading partners, and with the FDA, continues to be a key rallying cry for all those aiming to achieve 2023 interoperability.

Data System Management Challenges

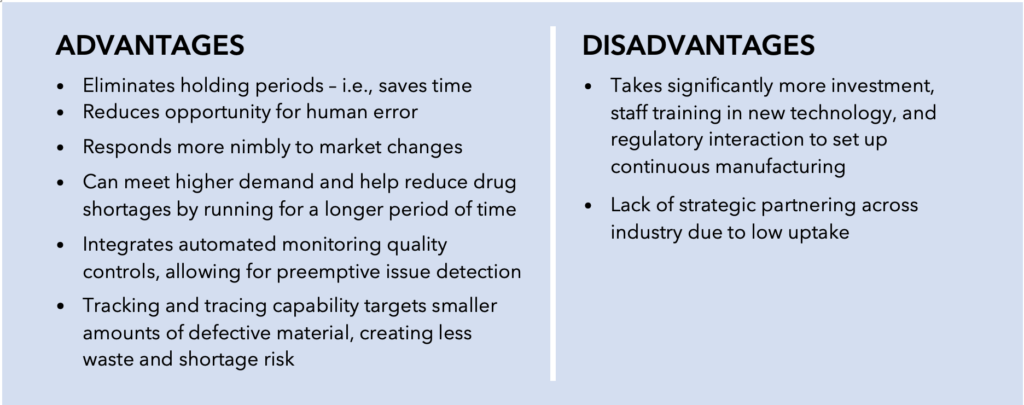

One discrepancy left unresolved in 2022 has been industry–FDA incongruence on an envisioned traceability data system architecture.20 The FDA recommends that industry adopt a distributed or semi-distributed data system architecture, which allows trading partners to maintain control over their own data in local databases.21 In contrast, a centralized data system manages supply chain-wide traceability data in a central repository or database. While industry and the FDA align on a distributed or semi-distributed management approach, they misalign on the capabilities of such a system.

For example, FDA draft guidance describes its recommended “enhanced system” as one that “should enable trading partners to share relevant data…upon request by an authorized trading partner, the FDA, or other appropriate Federal or State official.” Such a system suggests direct interface of regulatory authorities with individual trading partner systems (i.e., something leaning more toward a semi-distributed structure). Industry has asserted that such a system does not exist, nor can it feasibly be built in time for 2023.22 Additionally, industry has expressed concern about the degree of access the FDA’s system, as articulated, could afford the agency and state authorities.23 Instead, industry views the enhanced system being built as a network of independent trading partner systems and processes, not as a single system or technology (i.e., something leaning more towards a true distributed structure). Under this system, access to traceability data as part of interoperable exchanges is not viewed as direct access, but rather, is intermediated by individual trading partners through request and response functionalities.

This misalignment does not bode well for 2023 interoperability aspirations. Particularly in scenarios when trading partners may manage their data inconsistently from one another, risking technical challenges and interoperability breakdown when they go to exchange requested data. To better harmonize, stakeholders have called for more guidance on the management of traceability data at facilities.24 Better equipping trading partners with information on data management may be a huge part of actualizing interoperability of the whole system. Thus, information from the FDA in this regard will be something to look for down the 2023 stretch.

Conclusion

The path to DSCSA implementation has been a long and winding one. While signs of readiness have been observed, it’s also clear that many trading partners are still lagging in bringing together their capabilities in order to meet 2023 interoperability goals. Interoperability means a system that is wholly connected and cohesive — any missing links in the system will not only run counter to the intent of the DSCSA but could also stymie broader efforts to increase supply chain resiliency and to prevent drug shortages in the face of ongoing public health emergencies. Collaboration between and among trading partners and the FDA continues to top challenges faced in DSCSA implementation — both in working out technical issues at the local level, and in deepening stakeholder understanding about roles and responsibilities throughout supply chains. Additionally, greater insight into data management at facilities may help trading partners zero in on how traceability data should be transferred to, or accessed by, other trading partners or regulating authorities as part of the overall enhanced system.

References

- Title II of Public Law 113-54, “Drug Supply Chain Security,” (November 2013), available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-113publ54/pdf/PLAW-113publ54.pdf. See also, FDA Webpage, “Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA)”, available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-integrity/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa.

- FDA DSCSA Guidance & Policies Webpage, available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa/drug-supply-chain-security-act-law-and-policies.

- HDA Research Foundation, “Serialization Readiness Survey: Executive Summary”, (October 2022) available at https://www.hda.org/~/media/pdfs/center/2022-serialization-survey.ashx.

- Docket, FDA-2020-D-2024, available at https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2020-D-2024-0005/comment. See also, Regulatory News, “Industry calls for withdrawal of FDA electronic tracing guidance” (September 2021), available at https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2021/9/industry-calls-for-withdrawal-of-fda-electronic-tr.

- FDA Announcement, “FDA announces proposed rule: National Standards for the Licensure of Wholesale Drug Distributors and Third-Party Logistics Providers” (February 2022), available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa/fda-announces-proposed-rule-national-standards-licensure-wholesale-drug-distributors-and-third-party?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery. See also, Docket, FDA-2020-N-1663, available at https://www.regulations.gov/docket/FDA-2020-N-1663/document.

- FDA Draft Guidance, “Verification Systems Under the DSCSA for Certain Prescription Drugs,” (March 2022), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/117950/download.

- See, Regulatory News, “FDA publishes two critical DSCSA draft guidances” (July 2022), available at https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2022/7/fda-publishes-two-critical-dscsa-draft-guidances.

- See supra, n.5.

- FDA Final Guidance, “Drug Product Tracing: The Effect of Section 585 of the FD&C Act Q&A,” (February 2022), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/89954/download.

- Docket (FDA-2020-N-1663), available at https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2020-N-1663-0001.

- HDA Comments, Docket (FDA-2020-N-1663-0033), (September 2022), available at https://www.regulations.gov/comment/FDA-2020-N-1663-0089.

- FDA Revised Draft Guidance, “Identifying Trading Partners Under the DSCSA,” (July 2022), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/159621/download.

- FDA Draft Guidance, “DSCSA Standards for the Interoperable Exchange of Information for Tracing of Certain Human, Finished, Prescription Drugs,” (July 2022), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/90548/download.

- GS1 US Webpage, About GS1 US, available at https://www.gs1us.org/who-we-are/about-us.

- FD&C Act, Sect. 582(h)(4)(A)(i).

- ICMRA Report, “Recommendations on common technical denominators for traceability systems for medicines to allow for interoperability” (August 2021), available at https://www.icmra.info/drupal/sites/default/files/2021-08/recommendations_on_common_technical_denominators_for_T&T_systems_to_allow_for_interoperability_final.pdf.

- FDA Event, “Public Meeting on Enhanced Drug Distribution Security at the Package Level Under the DSCSA” (November 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/public-meeting-enhanced-drug-distribution-security-package-level-under-drug-supply-chain-security.

- See supra, n.3.

- See supra, n.18.

- See, Regulatory News, “Industry calls for withdrawal of FDA electronic tracing guidance” (September 2021), available at https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2021/9/industry-calls-for-withdrawal-of-fda-electronic-tr.

- FDA Draft Guidance, “Enhanced Drug Distribution Security at the Package Level Under the DSCSA,” (July 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/149704/download.

- HDA Comments, Docket, FDA-2020-D-2024, available at https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2020-D-2024-0005/comment. See also, Regulatory News, “Industry calls for withdrawal of FDA electronic tracing guidance” (September 2021), available at https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2021/9/industry-calls-for-withdrawal-of-fda-electronic-tr.

- See supra, n.18.

- See supra, n.18.