Greenleaf Regulatory Landscape Series

In the seventh year of implementation of the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA), trading partners involved in manufacturing, repackaging, distributing, and dispensing pharmaceuticals in the U.S. (industry) continue to grapple with its requirements. The goal of the DSCSA, which was enacted in November 2013 under Title II of the Drug Quality and Security Act,1 is to produce a system that enhances national pharmaceutical supply chain security by implementing a fully interoperable and electronic system for securing and tracing products by November 2023.2 Trading partner authorization, product tracing, verification, and product identification (including serialization) are four key components needed to achieve this goal.3

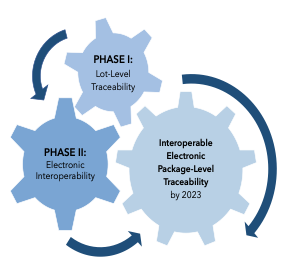

Since enactment of the DSCSA, two phases of implementation have been imposed. In the first phase, traceability requirements at the lot level were implemented beginning in 2015. In the second phase, interoperability requirements allowing for product tracing at the package level are scheduled to become effective in November 2023. Once in place, the interoperability requirements will involve: the exchange of transaction data by authorized trading partners; the ability of trading partners to verify products at the package level; and the maintenance of product tracing processes such that transaction data going back to the manufacturer can be provided upon request.4

The interoperability requirements, as opposed to the traceability requirements, are not clearly defined by the DSCSA, and yet, are particularly complex due to their electronic interconnectedness across the various industry sectors.5 As such, industry stakeholders have reported slow uptake of requirement testing and implementation thus far, which has been fueled by a lack of consistency, clarity, and awareness among trading partners, as well as added burdens related to the pandemic.6 Specifically, important testing of data systems by some manufacturers has not occurred at rates needed to ensure requirements are in place by 2023. Needed collaboration with trading partners, greater system governance, consistent DSCSA legal interpretation, and missing standards are all additional challenges weighing down implementation efforts.

FDA Efforts to Support Industry Readiness

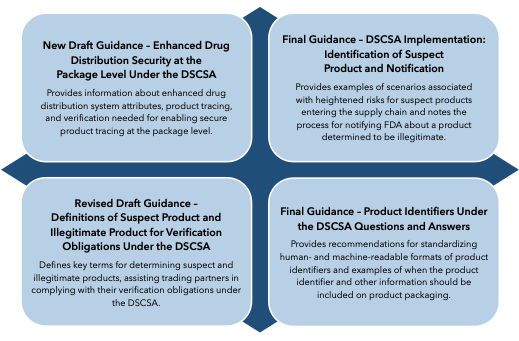

To help enhance industry’s overall readiness ahead of 2023, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA or Agency) released four guidance documents in June 2021 aimed at providing clarity and understanding around various DSCSA requirements.7 These guidance documents are summarized in Figure 2 below. The Agency also hosted multiple webinars in 2021 outlining key DSCSA requirements and explaining its new guidance documents and how they fit into the overall 2023 implementation scheme.8

Additionally, in February 2022, the FDA issued a proposed rule setting forth licensing standards for wholesale distributors and third-party logistics providers (3PLs), as mandated by the DSCSA.10 A national licensing system for distributors and 3PLs falls under the law’s key requirement that trading partners involved in the exchange of prescription drugs must be authorized such that they are appropriately registered or licensed to receive or transfer products.11 Establishment of national licensing standards eliminates an existing patchwork of state standards and is meant to provide industry-wide uniformity to better ensure all trading partners along supply chains are appropriately qualified to distribute prescription drugs. Diverging from its initial position issued in a 2014 draft guidance, the FDA’s proposed rule preempts state licensing laws that establish stricter standards, meaning that states can only continue licensing distributors and 3PLs if they match federal requirements.12 Once the rule is finalized, wholesale distributors will have two years, and 3PLs will have one year, before requirements take effect. Stakeholders have until June 2022 to comment on the proposed rule.13

Remaining Implementation Challenges: A Need for Further Clarity and Alignment

Despite new guidance and key implementation updates provided by the Agency, industry has continued to call for stronger alignment and the provision of more information around interoperability requirements. At a November 2021 public meeting,14 industry stakeholders called for the finalization of draft guidance on standards for secure, interoperable exchanges of product data and the endorsement of the global GS-1 standard for creating and sharing transaction data, or Electronic Product Code Information Services (EPCIS).15 The FDA has given assurance that finalized guidance is forthcoming.16 The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, as amended by the DSCSA, mandates17 that the FDA recommend data exchange standards that comply with those of widely recognized international organizations in order to facilitate the adoption of secure, interoperable, electronic data exchange along pharmaceutical distribution supply chains.18 Draft guidance released in November 2014 recommended the use of EPCIS, but also mentioned other methods and standards that could be used as well.19 The lack of a finalized standard recommendation has made many in industry reticent to begin implementing and testing data exchange systems, which are essential for ensuring systems are ready to go live in November 2023

Additionally, in Fall 2021, a number of industry stakeholders submitted comments expressing concern for perceived inconsistencies between the track and trace system put forth in new draft guidance and the plain language of the DSCSA, as well as a lack of other important information about requirements for 2023 compliance.20 The new draft guidance, “Enhanced Drug Distribution Security at the Package Level Under the DSCSA,” sets out the Agency’s decision as to whether data security system structures should be centralized or distributed, backing a distributed/semi-distributed model based on the idea that this approach allows trading partners to maintain control over their own data.21 Industry and other stakeholders disagree, however, as to whether this is the right approach for achieving interoperability. An August 2021 report from the International Coalition of Medicines Regulatory Authorities (ICMRA) promoted a centralized model as the “most efficient and simple” design for storing and reporting traceability data from multiple entities (although, the report also noted that “it is perfectly possible […] to design a system with distributed databases where each originator stores their own data”).22 In comments submitted to the new draft guidance docket, the Healthcare Distribution Alliance (HDA) stated that it did not believe a distributed or semi-distributed model is feasible, noting that what currently exists is “an ecosystem … of thousands of privately owned and maintained systems that are all different” (emphasis added).23

Other comments submitted to the docket reiterated HDA’s concerns with the new draft guidance, and also addressed concerns related to the sharing of proprietary information between trading partners and government authorities/other trading partners.24 In calling for the withdrawal of the draft guidance, and noting discussed challenges and concerns, HDA and other stakeholders expressed uncertainty as to industry’s ability to meet implementation requirements of the proposed electronic system in time for the 2023 deadline.25 Despite this looming deadline, the FDA has maintained that its planned electronic, interoperable track and trace system will go live in November 2023.26

Conclusion

The FDA has stressed that a system for enhancing drug distribution security will need to be robust, yet flexible.27 The Agency has also said it will leverage a range of coordinated mechanisms, such as: standardized data; standardized data exchanges; data analyses; investigations of suspect and illegitimate products; and other compliance guidance documents and enforcement tools.28 The complexity involved in achieving full implementation of the DSCSA is apparent and has been exacerbated in recent years by the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, greater industry understanding about requirements through additional guidance and communication from the FDA will be an important part of breaking down remaining challenges to full DSCSA implementation in 2023.

- H.R. 3204, Sec. 201, “Drug Supply Chain Security,” (November 2013), available at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-113publ54/pdf/PLAW-113publ54.pdf. See also, FDA Webpage, “Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA)”, available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-integrity/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa.

- CDER SBIA Virtual Compliance Conference, Connie Jung, RhP, PhD, “Enhancing Drug Distribution Security under DSCSA” (January 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/cder-compliance-conference-01142021-01142021.

- Id.

- Partnership for DSCSA Governance, “DSCSA 2023 Requirements,” available at https://dscsagovernance.org/.

- Id.

- RAPS Focus, “Panelists: Sluggish pace of DSCSA testing is worrisome” (May 2021), available at https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2021/5/supply-chain-members-concerned-over-sluggish-testi?utm_source=MagnetMail&utm_medium=Email%20&utm_campaign=RF%20Today%20%7C%204%20May%202021.

- FDA In Brief, “FDA provides new guidance to further enhance the security of prescription drugs in the U.S. supply chain” (June 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-brief-fda-provides-new-guidance-further-enhance-security-prescription-drugs-us-supply-chain?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery.

- See, CDER SBIA Virtual Compliance Conference, Connie Jung, RhP, PhD, “Enhancing Drug Distribution Security under DSCSA” (January 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/cder-compliance-conference-01142021-01142021; and CDER SBIA Webinar, Connie Jung, RhP, PhD, “Enhanced Drug Distribution Security in 2023 Under the DSCSA,” (October 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/enhanced-drug-distribution-security-2023-under-dscsa-10052021-10052021.

- See, FDA Draft Guidance, “Enhanced Drug Distribution Security at the Package Level Under the Drug Supply Chain Security Act,” (June 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/149704/download; FDA Final Guidance, “Drug Supply Chain Security Act Implementation: Identification of Suspect Product and Notification” (June 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/88790/download; FDA Revised Draft Guidance, “Definitions of Suspect Product and Illegitimate Product for Verification Obligations Under the DSCSA” (June 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/111468/download; and FDA Final Guidance, “Product Identifiers Under the DSCSA Questions and Answers” (June 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/116304/download.

- FDA Announcement, “FDA announces proposed rule: National Standards for the Licensure of Wholesale Drug Distributors and Third-Party Logistics Providers” (February 2022), available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa/fda-announces-proposed-rule-national-standards-licensure-wholesale-drug-distributors-and-third-party?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery.

- See, supra n.8.

- Docket, FDA-2020-N-1663, available at https://www.regulations.gov/docket/FDA-2020-N-1663/document.

- Id.

- FDA Event, “Public Meeting on Enhanced Drug Distribution Security at the Package Level Under the DSCSA,” (November 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/drugs/news-events-human-drugs/public-meeting-enhanced-drug-distribution-security-package-level-under-drug-supply-chain-security#event-materials.

- RAPS Focus, “FDA urged to endorse EPCIS to spur manufacturers’ uptake of DSCSA” (November 2021), available at https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2021/11/fda-urged-to-endorse-epcis-to-spur-manufacturers-u.

- FDA Draft Guidance, “Enhanced Drug Distribution Security at the Package Level Under the Drug Supply Chain Security Act,” (June 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/149704/download at p.6.

- FD&C Act, Sect. 582(h)(4)(A).

- See, supra n.16.

- Id.

- Docket, FDA-2020-D-2024, available at https://www.regulations.gov/document/FDA-2020-D-2024-0005/comment. See also, RAPS Focus, “Industry calls for withdrawal of FDA electronic tracing guidance” (September 2021), available at https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2021/9/industry-calls-for-withdrawal-of-fda-electronic-tr.

- FDA Draft Guidance, “Enhanced Drug Distribution Security at the Package Level Under the Drug Supply Chain Security Act,” (June 2021), available at https://www.fda.gov/media/149704/download.

- ICMRA Report, “Recommendations on common technical denominators for traceability systems for medicines to allow for interoperability” (August 2021), available at https://www.icmra.info/drupal/sites/default/files/2021-08/recommendations_on_common_technical_denominators_for_T&T_systems_to_allow_for_interoperability_final.pdf.

- See, supra n.20.

- Id.

- Id.

- RAPS Focus, “FDA official: Agency will not extend 2023 DSCSA interoperability deadline” (August 2021), available at https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2021/8/fda-stands-firm-on-november-2023-interoperability.

- See, supra n.2.

- Id.