Greenleaf medical device experts Dan Schultz, M.D., and Samantha Eakes, M.P.H., participated in a webinar with NyQuist AI Founder & CEO Michelle Wu that focused on opportunities for using Generative AI in regulatory affairs. The webinar — offered through the Regulatory Affairs Professional Society (RAPS) — included discussion from our experts about practical approaches that regulatory professionals in the life sciences can take to better navigate the uncertainties of Generative AI and maximize its potential.

Facing the Cross-Labeling Conundrum

Greenleaf’s combination products expert, Mark Kramer, was interviewed by the executive editor of Market Pathways, David Filmore, on the topic of cross-labeled combination products—in particular, how companies can navigate the associated challenges, and the potential for the FDA and Congress to clarify the regulatory ambiguities surrounding this issue. The piece can be read below or downloaded through the link at right.

The Question: Is Your Device … Not Just a Device?

Let’s say your company is developing a new twist on a catheter or an updated iontophoresis device. Your route to showing substantial equivalence to a predicate seems passable and you’re feeling optimistic.

But as you engage with FDA, the regulatory path takes a dramatic swerve. In the agency’s view, it turns out, the product is not a routine 510(k) device, but a device constituent part of a “cross-labeled combination product.” That means the drug center, not CDRH, will likely be assigned to lead the review and your company may be expected to submit a drug application that it may be operationally or legally unable to pursue.

Mark Kramer, an executive VP at Greenleaf Health and the founding director of FDA’s Office of Combination Products, says this issue crops up more than many companies realize. He’s seen it with catheters, injectors, nebulizers, infusion pumps, and any other variety of drug delivery device.

“It happens a fair amount,” Kramer said in an interview. “I’m going to say at least 10% or more of my work involves situations where this either is a real issue or can be. The company will explain what they have in mind for a particular product. And right away my mind will just go to, ‘Sounds like a cross-labeling issue to me.’”

To be sure, it’s possible for a company to develop a delivery device that is viewed simply as a device. There are plenty of unfilled syringes and other generic products out there that fit the bill. The key deciding factors on a product’s regulatory fate are whether it is intended to be used only with an “individually specified” drug in a manner in which the device and drug are both required for the intended use, and, in particular, whether or not the drug would be used in a manner consistent with its approved labeling.

If FDA deems that the label of an approved drug needs to be updated to reflect, for instance, a new intended use, route of delivery, or dosage introduced by the device, or, more generally, if there is no drug approved to be delivered in the manner performed by the device, that’s when it becomes a combination product. And in these cases, FDA’s device review often plays second fiddle to vetting of the revised drug labeling. Even though the company may have no intention of making or marketing a drug and may not be working with the manufacturer of the drug, pursuing approval of the product would likely require the firm to submit a drug application.

At this point, Kramer says, the device firm may have no feasible path forward. It is not able to submit a supplemental new drug application to another company’s product, and FDA can’t compel a drug firm to work with a device company to support a cross-labeling submission.

This is an area riddled with regulatory ambiguities about exactly how and when the cross-labeling threshold is met, the consultant warns (more on that later). Still, a manufacturer benefits from understanding the risks of devices referencing drugs early in the development process so it has a chance to avoid or at least prepare for the regulatory barriers. In practice, Kramer says, many companies are taken by surprise. “If they find out that what they thought was a device is now going to be regulated as a drug … it’s like a whole different game than what they originally had planned for.”

Early Awareness Is Key

In Kramer’s view, any company developing a device that delivers, activates, or is intended to be used in conjunction with a drug or biologic in some manner should be thinking about and researching this issue. “I would first encourage companies that are in this space to at least explore the potential regulatory ramifications very early and then start thinking about ways that they could potentially be handled,” he says.

One key step to try to avoid getting stuck in the cross-labeling morass, he notes, is to “cast a wide net in researching approved drugs that might be suitable candidates for your device since it’s important that you can identify at least one approved drug for such use.”

Ultimately, a firm may need to consider adjusting the design and labeling of its device to find a feasible short-term regulatory path. “There may be steps you can take to either mitigate the issue somewhat … or perhaps avoid it completely with the right kind of thinking,” Kramer says.

Designing Around the Problem

Tweaking the design details of its device is one of the primary tools a manufacturer has at its disposal if it wants to steer clear of the combination product zone.

“A company may have its eye on an ultimate ‘prized indication’ that raises a cross-labeling concern but be able to avoid it at least initially by making the design suitable not only for that ‘prized’ indication but also for a more general use for which one or more currently available drugs are already approved,” Kramer suggests.

A hypothetical example might be a prospective device that incorporates a specially curved tip ideal for locally delivering a drug to an anatomical target that doesn’t conform to FDA labeling for the drug.

“You want the design of the device to be more generalizable in a way, so that it couldn’t only be used for that one unique indication,” Kramer explains. “So maybe you could look at having a variety of different shapes and then present that family of shapes as the product or have one design that perhaps avoids that tip somehow.”

Often this approach requires the firm to make some compromises for the sake of regulatory expediency. The company can start by gaining authorization for a more general use/design via a device submission pathway. Then, with a version of the product already on the market, it may be in a better position to seek approval for more specialized indications.

In addition to device design, manufacturers should also of course consider the proposed product labeling to ensure it doesn’t unnecessarily reference unapproved drug indications. But the labeling needs to be a credible representation of the device’s capabilities or FDA will challenge it.

“It can’t be in words only,” Kramer stresses. “If hypothetically the device had a unique tip or shape that was designed for use in a specific part of the body, you can’t just say that it’s intended more generally. The design must also be suitable for the purported, more general use.”

Don’t Go to FDA Too Early

Experts commonly advise companies developing new devices to get early input from FDA directly, via the pre-submissions process or otherwise, to be better prepared for what the agency will expect. In this case, however, Kramer cautions against seeking input from FDA prematurely. “I find that companies might sometimes go to FDA too early, before they have thought these issues through, and then they kind of get on a track that it might be difficult to get off of,” he notes.

If a company is working through design considerations and ends up moving toward more generalizable labeling for the device, it could find itself being challenged if it previously asked FDA about the more specialized, “prized” indication, as Kramer describes it.

“Once you’ve put it out there—maybe without realizing the regulatory ramifications—that your device is really intended for [use] X, it kind of gets hard to take that back,” he says. “Careful thought and strategy into the way you’re positioning your product to FDA—thought about the design, thought about how you’re describing the intended use—is important.”

Companies need to consider whether they even want to raise any specific questions with FDA about the prospect of cross-labeling. “Do they want to first put this idea in an FDA reviewer’s mind or wait to see if it arises and then further explore options with FDA?” Kramer poses.

In cases when it’s an obvious call, FDA’s device center is apt to tell the company right from the start that a device raises a cross-labeling issue and direct it to the Office of Combination Products to designate the proper lead review center. But if there are some ambiguities, as there often can be, FDA will more likely wait to consider the issue until it has been able to review the data and context more thoroughly as part of the pre-submissions or submission review process, Kramer suggests. This means that a company may not have clarity on whether cross-labeling will be required until sometimes relatively late in the review process.

Embracing Your Inner Combo Product

But a device firm can’t always avoid seeking an indication that qualifies as cross-labeling. If the point of a development effort is to advance therapy beyond the status quo, it might necessarily involve pushing drugs to different use cases not reflected in current labeling. If this is the case, a company has a few options.

When possible, an ideal strategy is to partner with the manufacturer of an approved drug that would be referenced. If the device firm can convince the drug maker to get behind the updated delivery mechanism and submit a companion drug application, that could lead to a more straightforward FDA process. “Many companies do that, and it’s the preferred approach,” Kramer says. “It just may not always be possible.”

There are an array of reasons why a drug firm may not be interested. The company could have concerns about known or unknown risks cropping up from a new use of its product, or it could even sense commercial risks if the device is intended to deliver the drug in a manner that, for instance, is more targeted and thus requires lower amounts of medicine per treatment.

If the drug firm won’t come on board, the other option, particularly in cases of off-patent, generic drugs, is for the device manufacturer to actually produce the drug and submit it (likely in the form of a 505(b)(2) application) in parallel to a device submission or to submit the device as part of the drug submission.

That seems like a high bar for a company that doesn’t have any experience with pharmaceutical manufacturing or submissions, but Kramer points out that the firm could work with a generic drug supplier to handle the actual production.

For certain devices that go beyond passive drug delivery to feature some sort of active treatment mechanism independent of the drug, there is a potential third option. For these types of cases, Kramer suggests, it’s possible the most efficient regulatory route might be to develop a more traditional combination product where the device is physically combined or co-packaged with the drug. If the company can make the case that the device is responsible for the combination product’s primary mode of action (the regulatory basis by which a combination product is assigned to an FDA product center), it could pursue a device submission (510(k), De Novo, or PMA) rather than drug application.

This approach obviously raises an array of potential challenges, but, Kramer says, “I have seen this in more than a handful of situations be an attractive way to pursue approval.”

The Imaging Model

Often, though, unless a company has a prearranged business partnership with a drug firm, none of these options are ideal.

“The conundrum of this cross-labeling issue has really been that some devices may have no pathway to get to market absent the cooperation of the drug sponsor,” Kramer laments.

FDA first took a stab at fashioning a solution to this conundrum when it organized a public meeting on the topic in 2005, just a few years after FDA formed the Office of Combination Products under Kramer’s leadership. More recently, in 2017, FDA made a specific proposal to allow devices that raise cross-labeling issues to pursue the PMA pathway, rather than a drug application, as long as the device maker can independently demonstrate safety and effectiveness of the drug, establish an appropriate postmarket plan, and meet other requirements. FDA ultimately abandoned the plan, facing pushback from the pharmaceutical industry on multiple legal and logistical fronts.

During the same period, however, Congress enacted a pathway for one set of devices that could serve as a model to resolving this issue more broadly over the longer term. The 2017 FDA Reauthorization Act includes a provision responding to a long-held frustration by imaging device manufacturers about their inability to seek authorization through the device center for imaging equipment updates and new applications that don’t align with drug labeling of approved contrast agents. The FDARA provision now allows such modifications to proceed via a PMA, 510(k), or De Novo as long as the device company can show the update does not adversely affect the safety and effectiveness of the contrast agent when used with the device.

To be clear, this is far from a free pass for imaging manufacturers. Kramer is aware of at least one De Novo authorization, for a linear accelerator/PET system, that leveraged the FDARA provisions. The special controls established under the De Novo decision not only require makers of these devices to perform clinical testing and analysis, but it also requires sponsors to establish a postmarket plan to monitor for labeling and formulation changes to the contrast agent and how they will impact safety and effectiveness when used with the device.

“You still have to do the work,” Kramer affirms, but, the point is, it provides a possible pathway. “I think this is an attractive approach that’s now set out in the law. For me, I guess the question is, ‘Why can’t we do something similar for all the rest of the [non-imaging] products that are in this situation?’”

Closing Message: Clarity Is Needed

A broader legislative solution is unlikely in the near term. But Kramer has some hope that FDA will at least help clarify the current regulatory framework sooner rather than later. FDA Office of Combination Product officials have made public statements suggesting a guidance on cross-labeling is in the works, he says.

It would be helpful simply for FDA to more precisely define some basic terms and concepts included in the regulatory definition of cross-labeled combination products, to support more consistent decision-making by FDA reviewers and more predictability for manufacturers, Kramer notes.

For instance, the regulation says a device that might be subject to cross-labeling rules is intended for use “only with an approved individually specified” drug or biologic. But the consultant says it remains unclear whether that means a device label must reference a specific brand name of a drug or if the cross-labeling requirement applies to a device that references a generic drug name, which could be sold by many companies.

There is also a lot ambiguity about what level of inconsistency is acceptable between a device and drug label and which specific sections of the drug label are subject to the cross-labeling rules. The regulation specifically mentions intended use, dosage, and route of administration, among others, as areas of the drug label where a cross-labeling requirement is triggered if a device requires a change, but the wording suggests that it is not intended to be a comprehensive listing.

For instance, if a drug label details specialized training for providers that employ the medicine, but a device is developed to make the drug simpler to deliver without the training, does the training statement in the drug label need to be revised to allow clearance of the device? That is one example of a gray area offered by Kramer and a co-author in a recent article in the Regulatory Affairs Professionals Society’s Regulatory Focus publication, in which they call for more regulatory and legal clarity in this area.

“It’s a jumble of words that you really have to dissect carefully,” Kramer says about the current regulatory language. “In general, there’s not a really good appreciation of what the definition of a cross-label product means.”

Kramer had hoped an FDA guidance might be published on the topic as early as this year, but it’s not clear that timing will be met. For now, the best that companies can do is to appreciate the issue as an important consideration and at least avoid getting blindsided late in the regulatory process.

Companies will “back into this situation unwittingly sometimes because they think, ‘Well, I’m not doing anything with the drug. It’s simply a device,’” Kramer says. “It could really cause companies to go back to the drawing board.”

Filmore, David. Consultants Corner, “Facing the Cross-Labeling Conundrum With Mark Kramer.” Market Pathways. Vol 5.8; September 2023. p. 34-7. Published by MedTech Strategist. Published online September 19, 2023, at www.MyStrategist.com/market-pathways/article/consultants_corner_facing_the_cross-labeling_conundrum_with_mark_kramer.html.

Cross-Labeled Combination Products: A Regulatory Conundrum Awaiting a Solution

This piece was published online in Regulatory Focus, a RAPS publication, in July 2023. It is available to download via the link at right. RAPS members may also read the article on the RAPS website.

When a device is intended for use with an already approved drug in a manner that is not consistent with the drug’s approved labeling, regulatory challenges frequently emerge in determining whether the drug labeling must be changed to reflect its use with the device. This article highlights some of the unique regulatory considerations associated with cross-labeled combination products, particularly devices referencing drugs, in anticipation of an expected U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance document this year.

Kramer M, Hilscher S. Cross-labeled combination products: A regulatory conundrum awaiting a solution. Regulatory Focus. Published online 31 July 2023. https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2023/7/cross-labeled-combination-products

Update on Ongoing User Fee Negotiations

Greenleaf Regulatory Landscape Series

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA or the Agency) user fee programs help to provide funding for the Agency to achieve its mission of protecting the public health and providing safe and effective medical products to patients in the United States.1 The user fee programs provide the FDA with financial support to meet specified performance goals and commitments related to medical product submissions. These specific performance goals and commitments are negotiated and agreed upon between the FDA and industry in the years leading up to the reauthorizations and must be sent to Congress for review and approval.

All medical product user fees are renegotiated every five years. As the Prescription Drug User Fee Amendments (PDUFA VI), the Biosimilar User Fee Amendments (BsUFA II), and the Medical Device User Fee Amendments (MDUFA IV) are also set to expire on September 30, 2022, it is expected that all three user fee program extensions will be part of the same legislative package.2,3 The next set of authorizations for these programs will cover Fiscal Years 2023 to 2027.

Below is a summary of the current status of the PDUFA, BsUFA, and MDUFA negotiations as well as a description of the key commitments being discussed between the FDA and industry.

PDUFA

PDUFA VII will build upon the progress of past programs by providing the FDA with the resources and tools it needs to keep pace with advances in drug development. Considering recent scientific breakthroughs in cell and gene therapy and the bolus of investigational new drug (IND) applications for advanced biological therapies received by the Agency, PDUFA VII seeks to provide the Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) with the funding and authority to hire additional staff to meet this demand. With negotiations being held virtually against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, PDUFA VII also aims to formalize some of the lessons learned from the pandemic, including guidance and workshops on the use of alternative tools to assess manufacturing facilities and additional resources to support the broader use of digital health tools (DHTs). The commitment letter,4 which was made public in late August 2021, includes the following commitments:

Strengthen Scientific Dialogue. Recognizing the need for further dialogue between the Agency and sponsors, the FDA will formalize the INTERACT meeting framework as well as establish a similar meeting type for the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Both industry and the FDA also discussed the possibility of sharing metrics related to all PDUFA meeting types and associated interactions.

Promote Innovation. To shorten review timelines for certain approved therapies and support efficacy endpoint development for rare diseases, PDUFA VII will establish the Split Real Time Application Review (STAR), modeled after CDER’s Real Time Oncology Review (RTOR).5

Support Advanced Biological Therapies. As noted, CBER will likely be provided dedicated resources to ensure the timely review of all applications for innovative biological therapies. Negotiations also focused on including the patient voice in gene therapy development programs as well as the potential for a workshop on how sponsors could leverage prior knowledge to accelerate gene therapy development. The FDA and industry also discussed a proposal on potential guidance dedicated to clarifying evidentiary standards for the RMAT program.6

Modernize Evidence Generation and Drug Development Tools. To advance the use of real-world evidence (RWE), both industry and the Agency discussed the establishment of a pilot program to develop new methods for using real-world data (RWD) in regulatory decision-making, including in the review of applications.7 Both industry and the FDA expressed an interest in continuing the Model Informed Drug Development (MIDD) paired meeting program. Issuance of guidance related to Complex Innovative Designs (CID) is also included in the commitment letter.8

Advance IT Infrastructure. PDUFA VII will also modernize data and information technology (IT) capacity and capabilities, including the adoption of cloud-based technologies as described in the FDA’s Technology Modernization Action Plan as well as technology convergence across the review centers more broadly.9 Both industry and the FDA also discussed potential programs and initiatives that could inform the evaluation of DHT-generated data.10

Next Steps

The initial draft of the PDUFA commitment letter has been published and is currently open to comment.11 The letter will also be reviewed and discussed at a public meeting on September 28, 2021.

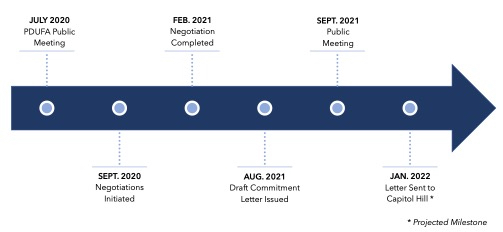

PDUFA VII Negotiation Process

BsUFA

With negotiations recently completed on the heels of the PDUFA VII negotiations, BSUFA III will likely include several commitments that were agreed to in PDUFA VII, such as the development of guidance on alternative tools to assess manufacturing facilities, the dedication of resources to modernize the FDA’s data and information technology capabilities, and resources to enhance hiring and retention. Additional focus areas from the BSUFA III negotiations are outlined below:

Greater Collaboration Between Sponsors and the FDA. To improve collaboration between the Agency and sponsors, the commitment letter will likely include a new Biosimilar Biological Product Development (BPD) meeting type in which the Agency can provide focused targeted feedback. Modifications to the timelines and processes for Type 4 meetings are also likely.12

Regulatory Science Program. To facilitate more efficient biosimilar and interchangeable product development, as well as enhance regulatory decision-making, both the FDA and industry appeared to have agreed to funding a BsUFA Regulatory Science Program, modeled on the successful GDUFA Regulatory Science Program.13

Expedited Application Review. During negotiations, industry and the FDA discussed best practices for application review and opportunities for implementing those best practices into FDA documents and procedures.14

Next Steps

The BsUFA commitment letter is currently being reviewed by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Office of Personnel Management, and the Biden Administration. The BsUFA letter will also be open to public comment and discussed in a public meeting, likely to be held in mid-fall 2021, before being sent to Capitol Hill.

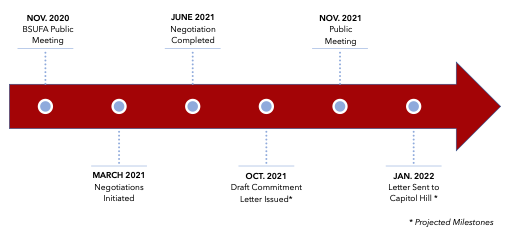

BsUFA III Negotiation Process

MDUFA

The MDUFA V negotiations have also been shaped by the experience of the FDA, industry, and other stakeholder groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. Both the FDA and industry want to keep elements of the regulatory flexibility that was provided during the pandemic as well as the increased amount of interaction between sponsors and the Agency. Additionally, for MDUFA V, both groups want to carry over many of the commitments and goals that were set during MDUFA IV. This approach aims to help maintain the status quo and ensure stability and continuity for the premarket review program in light of the many adjustments that the Agency had to make to manage the additional workload brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. This approach will also provide additional time to achieve some of the commitments outlined in MDUFA IV that have not yet been met.15

Several proposals made by each group during the MDUFA V negotiations are still under discussion. These proposals include the following:

Hiring Targets and Vacancies. Throughout the negotiations there has been significant discussion regarding the number of vacancies for full-time equivalent (FTE) staff positions tied to user fees and the salaries for these positions. As part of MDUFA V, industry has proposed that annual specific numerical hiring targets be set in order to increase the formality of these goals, including increased transparency and prioritization by the Agency.16

Review of MDUFA IV One-Time Costs. Industry has proposed a review of funding for one-time costs from MDUFA IV including renewing funding for certain programs but not others. More specifically, industry would like to continue funding for “initiatives for patient engagement, recruitment, retention, and the independent assessment” while not renewing as part of MDUFA V funding “the investment to stand up time reporting” or “the IT investment to support digital health.” Other programs would require further discussion in order to be extended with MDUFA V funding, including “IT enhancements for premarket review work; real-world evidence; standards conformity assessment; and third party review.” In addition, industry has proposed to reinstate 5th year offset fees as the carryover balance has grown to a significant level.17

Device Safety. The FDA has presented a proposal to enhance its capabilities related to postmarket surveillance to allow the Agency “to more accurately and precisely identify the scope of potential concerns, to more efficiently resolve device performance and patient safety issues, and to provide timely and clear communications with patients and healthcare providers.”18 Although industry supports these enhanced capabilities, they noted during the negotiations that MDUFA funding has statutorily been limited to only premarket activities, and this significant change for industry-based funding would require statutory changes.

The Total Product Life Cycle Advisory Program (TAP). The FDA has presented the TAP program as a new model for frequent and rapid FDA interaction with sponsors that would also provide valuable feedback from external stakeholders such as payers and providers. The FDA described the program as including the hiring of new premarket review staff with different levels of expertise as well as inviting external stakeholder groups to participate in the process. The FDA also explained that the program aims to provide a more iterative engagement process with sponsors that could lead to higher quality submissions and fewer review cycles. Industry has voiced serious concern that many elements of the TAP program as currently outlined, such as convening private payers, seem to go beyond the scope of MDUFA and could require statutory changes. Industry is also concerned that this model could lead to more complex reviews and thereby increased program costs. Lastly, industry noted that there are already several FDA premarket programs that provide sponsors with increased engagement with the FDA as well as opportunities to discuss coverage with payers.19

Next Steps

The FDA and industry will continue to meet throughout the coming year to develop an agreed-upon commitment letter to present to Congress. All stakeholder groups are encouraged to participate in the ongoing public negotiations. The most recent FDA-industry meeting was scheduled for May 19, 2021, but meeting minutes have not yet been published.20 Public records also show that several additional stakeholder consultation meetings were scheduled through the end of August.21

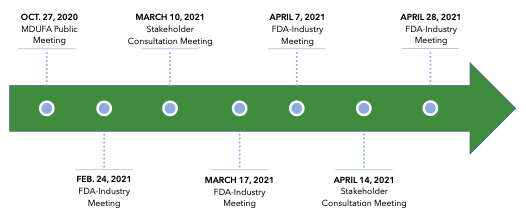

MDUFA V Negotiation Process22

1. Food and Drug Administration Website, FDA User Fee Programs, https://www.fda.gov/industry/fda-user-fee-programs.

2. Although not discussed in this memo, the Generic Drug User Fee Act (GDUFA) has the same end date and will likely be a part of the same legislative package as PDUFA, BsUFA, and MDUFA.

3. Derek Gingery, “PDUFA VII Negotiations Completed, Commitment Letter Ratification Ongoing,” Pink Sheet, 22 March 2021, https://pink.pharmaintelligence.informa.com/PS144034/PDUFA-VII-Negotiations-Completed-Commitment-Letter-Ratification-Ongoing.

4. FDA, PDUFA VII Commitment Letter, August 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/151712/download.

5. PDUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry Pre-Market Subgroup, 27 January 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/147552/download.

6. PDUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry CBER Breakout Subgroup, 10 November 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/145588/download.

7. PDUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry Pre-Market Subgroup, 21 January 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/147564/download.

8. PDUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry Negotiation Regulatory Decision Tools Subgroup, 1 December 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/146389/download.

9. PDUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry Digital Health and Informatics, 27 January 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/146779/download.

10. PDUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry Digital Health and Informatics, 16 December 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/146775/download.

11. FDA, PDUFA VII Commitment Letter, August 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/151712/download.

12. BSUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry Steering Committee Meeting, 27 April 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/149026/download.

13. BSUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry Steering Committee Meeting, 13 April 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/148185/download.

14. BSUFA Reauthorization Meeting Summary, FDA and Industry Steering Committee Meeting, 20 April 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/149025/download.

15. Meeting Minutes, FDA–Industry MDUFA V Reauthorization Meeting, 28 April 2021, https://www.fda.gov/media/150625/download.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. FDA Webpage, Stakeholder Consultation Meetings – Medical Device User Fee Amendments 2023 (MDUFA V), https://www.fda.gov/industry/medical-device-user-fee-amendments-mdufa/stakeholder-consultation-meetings-medical-device-user-fee-amendments-2023-mdufa-v.

22. FDA Webpage, Medical Device User Fee Amendments 2023 (MDUFA V), https://www.fda.gov/industry/medical-device-user-fee-amendments-mdufa/medical-device-user-fee-amendments-2023-mdufa-v.

In Vitro Diagnostic EUAs for COVID-19

Greenleaf Regulatory Landscape Series

On February 4th 2020, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) declared that the threat to public health caused by the coronavirus justified the authorization of emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection and/or diagnosis of COVID-19. This declaration, pursuant to section 564 of the Food Drug & Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act), allowed the Commissioner of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA or Agency) to issue Emergency Use Authorizations (EUAs) for developers of in vitro diagnostic tests aimed to detect and/or diagnosis COVID-19.

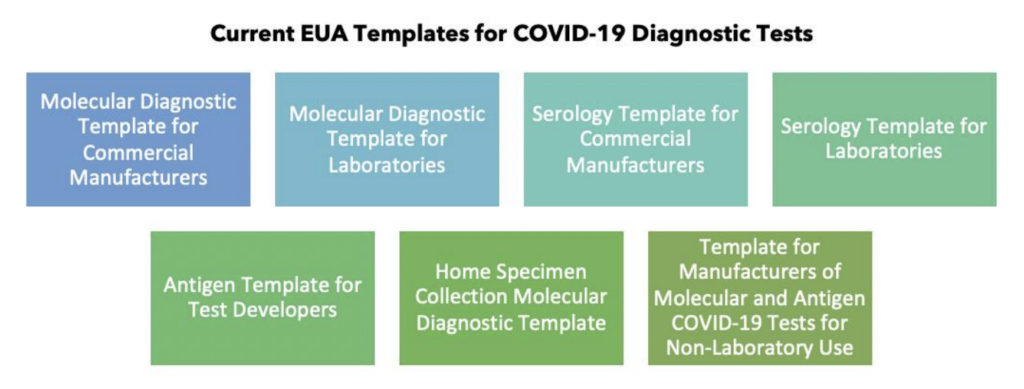

Following the declaration, the FDA began to receive a sudden flurry of EUA requests from diagnostic test developers before truly having an opportunity to develop its own guidance and recommendations for laboratories, manufacturers, and FDA staff. The FDA quickly developed guidance that outlined what specific tests required EUA authorization prior to marketing, what tests could use the notification pathway, and what validation and clinical testing was required for an EUA. The Agency focused on the authorization of molecular, antigen and antibody (serology) tests and informed healthcare providers and the public as to the type of information that each test could provide. As more became known about COVID-19 and as tests were in shortage across the United States, the FDA continued to evolve its regulatory framework and recommendations for in vitro diagnostic EUAs including publishing a revised guidance on its “Policy for Coronavirus Disease-2019 Tests During the Public Health Emergency.” Over the course of several months, the FDA published templates for both commercial manufacturers and laboratories for each of the three types of diagnostic tests and updated them with recommendations for the validation of pooled samples and the testing of asymptomatic individuals. The Agency also published templates for tests that use home specimen collection and for non-laboratory use tests.

Throughout the pandemic, the FDA has had to explore options to quickly allow diagnostic tests to reach patients while still ensuring that these tests are safe and effective. To enhance transparency around the FDA’s decision-making and to provide a forum for public questions, the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH) began holding weekly virtual Town Halls for developers of diagnostic tests. These Town Hall meetings have been led by Dr. Timothy Stenzel and Toby Lowe from CDRH’s Office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health. Each week, CDRH staff provides developers with an update on any major changes in the FDA’s policies related to diagnostic tests and provide insight on what changes may be coming in the near future. Dr. Stenzel has also expressed the Agency’s willingness to work with developers of novel technologies and to remain flexible in its regulatory approaches. CDRH has already held 30 Town Hall meetings for diagnostic test developers and has committed to holding these events throughout October 2020.

During the Town Hall meetings, Dr. Stenzel shared that the FDA has received more than 2,000 EUA requests from developers and explained the triage process that CDRH has developed in order to respond to these requests with the resources that the Agency has available. Recently, Dr. Stenzel noted that after issuing more than 200 EUAs for diagnostic tests, the FDA is now prioritizing EUA requests for specific types of tests including point-of-care tests, at-home tests, and tests with high-throughput capacity with ability to scale. He explained that the FDA is still taking EUA requests for tests that do not have these specific features but that they will receive lower priority in terms of review. Another major development that was recently announced during a CDRH Town Hall meeting is that CDRH will no longer be reviewing EUAs for Laboratory Developed Tests (LDTs). This comes after the Department of Health and Humans Services (HHS) published a notice in August stating that the FDA would no longer require premarket review of LDTs for COVID-19. Although HHS’s announcement stated that companies could still voluntarily submit EUA requests for LDTs, the Agency has since stated that it will no longer review them. Dr. Stenzel explained that this change was made to help focus the FDA’s resources on the EUAs that have been identified as priority. During last week’s Town Hall meeting, Dr. Stenzel noted that CDRH will soon be updating their FAQ pages to provide further clarity on how this policy will impact current LDT submissions and EUAs that are already authorized.

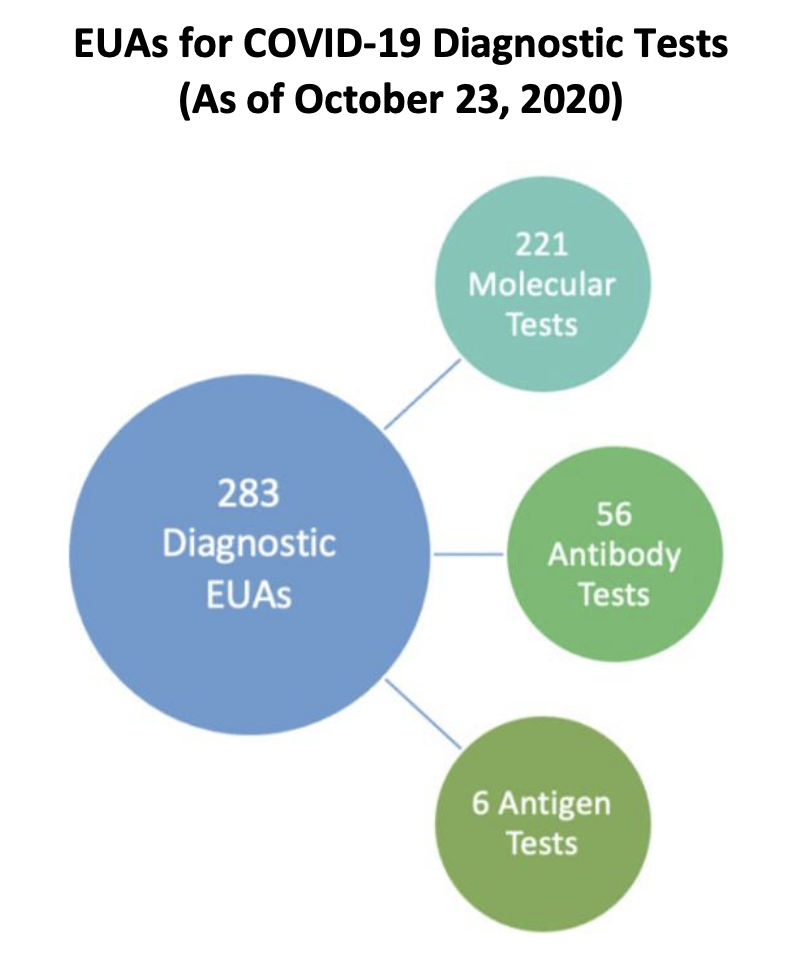

As of October 23, 2020, there are 283 EUAs that are authorized for COVID-19 diagnostic tests

including 221 molecular, 56 antibody and 6 antigen tests. FDA’s website also provides a complete list of all current EUA authorizations for the following EUA categories:

- Individual EUAs for Molecular Diagnostic Tests for SARS-CoV-2

- Umbrella EUA for Molecular Diagnostic Tests for SARS-CoV-2 Developed And Performed By Laboratories Certified Under CLIA To Perform High Complexity Tests

- Individual EUAs for Antigen Diagnostic Tests for SARS-CoV-2

- Individual EUAs for Serology Tests for SARS-CoV-2

- Umbrella EUA for Independently Validated Serology Tests for SARS-CoV-2

- Individual EUAs for IVDs for Management of COVID-19 Patients

Overall, the FDA has made significant progress in authorizing EUAs for COVID-19 diagnostic tests and has helped to facilitate access to these tests for patients across the United States. FDA’s regulatory policies will continue to be updated as the pandemic changes and as developers begin to transition their EUA authorizations to full premarket clearance or approval.

Related Sources

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Emergency Use Authorizations for Medical Devices

- Policy for Coronavirus Disease-2019 Tests During the Public Health Emergency (Revised)

- Virtual Town Hall Series – Coronavirus (COVID-19) Test Development and Validation

- Rescission of Guidances and Other Informal Issuances Concerning Premarket Review of

Laboratory Developed Tests - In Vitro Diagnostics EUAs

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) Update: Daily Roundup October 23, 2020

- A Closer Look at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health’s Unprecedented Efforts in

the COVID-19 Response