This article was originally published in Med Device Online.

As a result of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns and limited in-person healthcare opportunities, FDA (and other regulatory authorities) loosened restrictions on the oversight of digital health technologies (DHTs), and even began to encourage their use in certain settings. The expiration of the public health emergency (PHE) and the related unwinding of certain pandemic guidances that created a more permissible environment for DHTs have significant implications for the DHT landscape.

This article covers three guidances particularly salient to DHTs that may sunset this fall, but which are still critical to understand, as the principles enshrined in at least two of the guidance documents are likely to live on. More specifically, based on recent FDA draft guidances, communications from senior FDA leaders, and other sources, the agency appears to continue to recognize the value of DHTs, particularly in clinical trials and in home-based patient monitoring and healthcare management settings. Industry should take advantage of this opportunity to engage with the FDA as it develops the longer-term framework for regulation of DHTs.

Pandemic Health Emergency’s Expiration and Unwinding of Pandemic Guidances Relevant for DHTs

The COVID-19 PHE declaration and the related authorities it granted expired on May 11, 2023, and as a result, some guidances that FDA issued pursuant to those authorities sunset on that date or will sunset soon.1 FDA sorted the 72 COVID-19 related guidances that were in effect prior to the PHE expiry into four broad buckets:2

- 22 guidances that are no longer in effect as of the PHE declaration expiry on May 11, 2023 (“May Terminated Guidances”)

- 22 guidances that will continue in effect for 180 days after the PHE declaration expiry and then will no longer be in effect as of Nov. 7, 2023 (“November Terminated Guidances”)3

- 24 guidances that will continue in effect for 180 days after PHE expiry (until Nov. 7, 2023), during which time the agency plans to further revise these guidances and there may be a future sunset date or potentially these will remain in effect indefinitely (“Indefinitely Extended Guidances”)

- Four COVID-19 related guidances whose duration is not tied to the COVID-19 PHE and thus will remain in effect.

Several guidances related to digital health technologies are affected by the end of the PHE and fall into the November Terminated or Indefinitely Extended guidance category, which could have critical implications for DHT manufacturers.

Guidance on Mental Health DHTs

There is one guidance with implications for digital health technologies that falls into the second category of guidances terminating on Nov. 7, 2023, namely, CDRH’s Enforcement Policy for Digital Health Devices for Treating Psychiatric Disorders During the COVID-19 PHE (FDA-2020-D-1138).4

In brief, the guidance signaled that, for the duration of the PHE, the agency would not object to, or enforce against, the distribution and use of computerized behavioral therapy devices and other digital health therapeutic devices, with some caveats, for psychiatric disorders or for low-risk general wellness and digital health products for some mental health or psychiatric conditions.5 These psychiatric disorders included, but were not limited to, obsessive compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, insomnia disorder, major depressive disorder, substance use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, autism, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.6 The guidance also noted that the psychiatric condition could have been a condition existing prior to the pandemic or may have onset during the public health emergency.7 The guidance was issued with the explicit two-fold goals of (i) expanding the availability of DHTs for psychiatric disorders at a time when access to mental healthcare would otherwise have been limited and when mental health disorders were skyrocketing due to the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns and (ii) limiting patient and provider contact to minimize the spread of infection but still ensure patients received healthcare.8

This guidance will remain in effect until Nov. 7, 2023, unless superseded by a revised final guidance before that date. DHT companies, depending on the technology and stated policy caveats, may need to take action to remove their devices from the market or take steps to comply, such as submitting a marketing application. There are also important implications for patients and providers. Will patients who have come to rely on DHTs for access to mental health care be able to continue using existing options or seek out new treatments? Will they be able to switch seamlessly back to in-person provider-based care or forgo it if their access to DHTs is limited? These are open questions, but ones the agency will consider.

Clinical Trial-Related Guidances

In addition, two guidances particularly salient for the digital health industry fall into the bucket that will be revised before Nov. 7, 2023, to either sunset at a later date or continue indefinitely. One is CDER’s Guidance on Conduct of Clinical Trials of Medical Products during COVID-19 Public Health Emergency (FDA-2020-D-1106-0002).9 FDA’s goal in issuing this guidance was to provide general considerations and recommendations to help sponsors in ensuring the safety of clinical trial participants, maintaining compliance with GCP, and minimizing risks to trial integrity and interruptions for the duration of the COVID-19 PHE.10 The guidance included a lengthy question-and-answer section describing specific scenarios and how FDA would expect sponsors to handle them.11 For example, the guidance discussed when it would be appropriate to conduct remote clinical visits for trial participants; when to remotely monitor clinical sites to ensure both trial participants’ safety but also data integrity; or when and how to ship the studied product to a local healthcare provider to minimize trial participants’ travel and face-to-face contact with others.12

In fact, as we anticipated, the FDA released a final version of this guidance at the end of September, with a slightly different title to encompass a broader array of emergency circumstances: Considerations for the Conduct of Clinical Trials of Medical Products During Major Disruptions to Due to Disasters and Public Health Emergencies.13 The final guidance is similar to the COVID version, and recommends approaches that sponsors of clinical trials of medical products can consider when there is a major disruption to clinical trial operations during a disaster or public health emergency.

The other guidance is CDRH’s Enforcement Policy for Non-Invasive Remote Monitoring Devices Used to Support Patient Monitoring during the Coronavirus Disease Public Health Emergency (Revised) (FDA-2020-D-1138).14 This guidance was issued with the express hope of expanding the availability and capability of remote patient monitoring devices.15 Specifically, with the guidance, FDA signaled its enforcement policy would apply to an enumerated list of legally marketed non-invasive remote monitoring devices that measured or detected common physiological parameters and that are used to support patient monitoring during the PHE.16 Examples of covered devices would be a non-invasive blood pressure measurement system and a cardiac monitor, among others.17 Further, modified use of these covered devices would improve access to important patient physiological data “without the need for in-clinic visits and facilitate patient management by healthcare providers while reducing the need for in-office or in-hospital services” during the PHE, decreasing COVID-19 infection/contraction risks for patients and providers alike.18

Just recently, on October 19, the FDA revised the above as updated final guidance on its enforcement policy for remote patient monitoring devices. The new final guidance includes several revisions, or updates, compared against earlier versions. For example, the FDA removed the oximeter and clinical electronic thermometer device types that were listed in table enumerating legally marketed non-invasive remote monitoring devices. The FDA stressed that manufacturers of non-invasive remote monitoring devices the table must submit a premarket notification and receive clearance prior to marketing these devices in the U.S., to the extent the devices are not 510(k)-exempt, as well as comply with post-marketing requirements. The FDA also expressed its intention to allow limited modifications to the indications, functionality, or hardware or software of certain non-invasive remote monitoring devices used to support patient monitoring without prior submission of a premarket notification in certain examples. The examples provided were moving a subject device from the hospital or healthcare setting to the home or making a hardware or software change to improve remote monitoring of patients. Notably, this updated final guidance has no sunset or expiration date.

The Regulatory Landscape for DHTs in a Post-Pandemic World: Forward-Looking Possibilities

Although the expiry of the PHE means the future of the guidances discussed above is uncertain, lessons learned from the pandemic, and general themes embodied in the guidance documents described above, are consistent with FDA’s current vision for the DHT regulatory landscape. DHT developers and manufacturers should pay close attention to how FDA handles these guidances in November.

As such, we suggest that FDA may be inclined to extend these guidances indefinitely, or at least continue to implement the principles included within those guidances if they do sunset. This is particularly likely for the guidance on conduct of clinical trials and the enforcement policy for digital health devices for treating psychiatric disorders. One motivation for extending these guidances indefinitely is that they seem to fit with the agency’s general regulatory stance on increasing the availability, use, and reliance on DHTs in general, but particularly in clinical trial settings and for patients in home healthcare monitoring/home-based healthcare models.

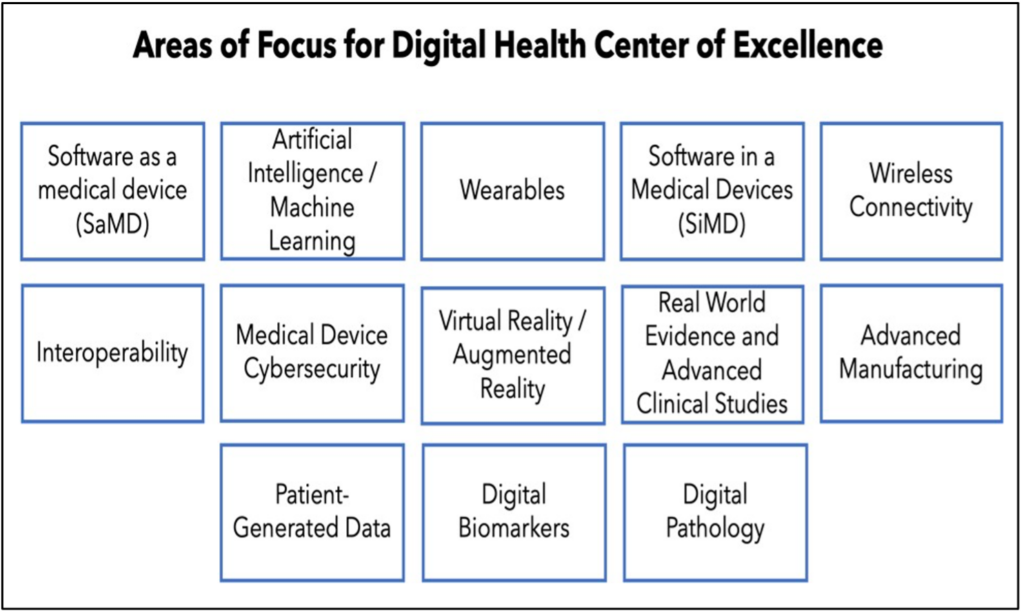

For example, the draft guidance on the conduct of clinical trials complements and is consistent with the March 2023 Framework for Digital Health,19 several other post-pandemic recent draft guidances, as well as statements from FDA senior leadership associated with the issuance of draft guidances, and other policy/strategy documents that the agency has released, among others.

More specifically, on June 6, 2023, FDA issued draft guidance from the International Council for Harmonisation on Good Clinical Practices (GCP) E6(R3) and opened the docket for public comment, with comments due by September 6.20 This FDA draft guidance (embodying the ICH guideline) aims to maintain a flexible GCP framework that ensures the safety of clinical trial participants and data, while also advancing new principles that modernize clinical trials and support more efficient approaches to trial design and conduct.21

One way the FDA guidance envisages modernizing clinical trials is encouraging the use of DHTs, particularly fit-for-purpose innovative DHTs.22 The draft guidance states: “[f]or example, innovative digital health technologies, such as wearables and sensors, may expand the possible approaches to trial conduct.”23 Additionally, the draft guidance stresses the fit-for-purpose nature of DHTs, stating that “the use of technology in the conduct of clinical trials should be adapted to fit the participant characteristics and the particular trial design. This guideline is intended to be media neutral to enable the use of different technologies for the purposes of documentation.”24

Equally important to the agency’s emphasis on using DHTs to modernize and decentralize clinical trials, the agency also has stressed the importance of DHTs for patient monitoring/home-based monitoring and care. It is theoretically possible – or maybe even pragmatic – for the agency to extend, revise, or potentially finalize guidance similar to the enforcement policy for digital health devices for treating psychiatric disorders.

Earlier this year, CDRH’s director, Jeff Shuren, gave an interview to Focus, a trade press publication. The interview, published June 16, focused on how the head of CDRH believes that “moving medical technologies from the clinical setting into the home may reduce costs and improve patient care; however, he cautioned that any medical technology used at home must prove that it is fit-for-purpose.”25 Specifically, one of his quoted statements described how the pandemic moved the agency to create “flexible policies to facilitate modifications to devices to have digital remote capabilities to help move care to the home or in some cases even the development of technologies without prior FDA review to be able to facilitate care in the home, some of the adjunctive behavioral therapies, for example.”26

His specific reference to the enforcement policy for digital health devices for treating psychiatric disorders27 guidance demonstrates its significance and that the guidance’s themes are part of, or at least consistent with, the center director’s vision for moving medical technologies into the home and the value of DHTs in doing so. After Director Shuren’s comments, FDA published a list of questions for public comment on what, and how, the agency can do to foster and incentivize the development of at-home DHTs and what factors should be considered when those technologies come to market.28 In particular, the questions include the following:

- “How can the FDA support the development of medical technologies, including digital health technologies and diagnostics, for use in non-clinical care settings, such as at home?

- What factors should be considered to effectively institute patient care that includes home-based care?

- What are ways that digital health technologies can (a) foster the conduct of clinical trials remotely and (b) support local or home-based healthcare models?

- How can the FDA facilitate individuals accessing medical technologies in remote locations when they are unable or unwilling to access care in clinical settings?

- What processes and medical procedures, including diagnostics, do you believe would be ideal for transitioning from a hospital and/or healthcare setting to non-clinical care settings, for example, home use or school/work use?

- What medical technologies could be ideal to transition to use in non-clinical settings? What aspects of those technologies could potentially benefit from modifications to optimize use in non-clinical settings?

- What design attributes and user needs would facilitate the use of medical technologies, including diagnostic and therapeutic devices, for use in a non-clinical setting, for example home use?

- For digital health technologies, what design attributes could better facilitate their use by diverse patient populations outside of a clinical setting? What other factors are important to consider which may improve use and acceptance of different digital health technologies by diverse patient populations (for example, older adults, non-English speakers, lower literacy)?

- What potential methods and strategies for evidence generation and data analysis could facilitate the regulatory review of medical technologies intended to be used in non-clinical settings, for example home use or school/work use?”29

CDRH’s request for public comment on increasing patient access to at-home use medical technologies, including DHTs, is consistent with CDRH’s broader effort to expand access to home use technologies, including as described, for example, in CDRH’s 2022-2025 Strategic Priority Document focused on advancing health equity.30 Indeed, moving medical technologies including DHTs out of the clinic or traditional healthcare settings into patients’ lives better meets patients where they are.

Conclusion

Expiration of the PHE and the unwinding of COVID-19 related guidances have major implications for FDA-regulated industry and products writ large but also specifically for DHTs. Some guidance documents relevant for DHTs will be in effect until at least November 7 and may be revised to continue indefinitely. However, even if these guidances are not revised or extended indefinitely, it appears FDA has taken “a lessons learned” approach from the pandemic use of DHTs in clinical trials and in at-home patient monitoring/healthcare to inform their vision for the future of the DHT regulatory landscape. As FDA aims to encourage the evolving innovation and technological progress, regulated industry, including DHT developers and manufacturers, should proactively seek opportunities to engage with FDA on DHTs and their use in clinical trials and in patient monitoring/home-based models of care. These technologies hold great promise for modernizing the conduct of clinical trials and for providing patient care.

References/Notes

- Fact Sheet, COVID-19 Public Health Emergency Transition Roadmap, https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2023/02/09/fact-sheet-covid-19-public-health-emergency-transition-roadmap.html. Note that there were 80 COVID-19 related guidances published; however, eight had already been withdrawn because they no longer reflected the agency’s current thinking.

- Guidance Documents Related to COVID-19, 88 Fed. Reg. 15417 (Mar. 13, 2023), https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/03/13/2023-05094/guidance-documents-related-to-coronavirus-disease-2019-covid-19.

- Note that guidances listed that are subject to the device enforcement policy transition guidance will continue in effect for 180 days after expiration of the PHE declaration unless a different intended duration for the guidance is set forth in the final device transition guidance or the guidance is otherwise superseded by a revised final guidance before that date.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/136939/download.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/136939/download.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/136939/download.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/136939/download.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/136939/download.

- Guidance available here, https://www.fda.gov/media/136238/download.

- See id.

- See id.

- See id.

- https://www.fda.gov/media/172258/download

- Guidance available here, https://www.fda.gov/media/136290/download.

- See id.

- See id.

- See id.

- Id. at 5.

- https://www.clinicaltechleader.com/doc/an-overview-of-fda-efforts-to-encourage-dht-use-in-drug-biological-product-development-0001

- FDA Draft Guidance on E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice, available here, https://www.fda.gov/media/169090/download. See the FDA Docket, available here, https://www.regulations.gov/docket/FDA-2023-D-1955?utm_source=dailyem,sfmc&utm_medium=email,email&utm_campaign=,Medtech%20Insight%20

Daily%20(Tues%20-%20Fri). Note that the draft guidance tracks with ICH’s recently updated E6(R3) draft guideline, and that guideline was drafted to describe how to deal with technological innovations for clinical trials, among other goals. - FDA Draft Guidance on E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice, available here, https://www.fda.gov/media/169090/download.

- Id. at 2.

- Id.

- Id.

- https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2023/6/shuren-at-home-technologies-must-be-fit-for-purpos?mkt_tok=MjU5LVdMVS04MDkAAAGMZTsbK1r5IMpvnhjfyNGby2h0mjBZwP2wpJ45zqW5JOeu

MFOFTh5GcCY90W3c3KbDVNCWeVLW1JsQ_8a2evANoJRN2mkYXZibZ0bzIuna. - https://www.raps.org/news-and-articles/news-articles/2023/6/shuren-at-home-technologies-must-be-fit-for-purpos?mkt_tok=MjU5LVdMVS04MDkAAAGMZTsbK1r5IMpvnhjfyNGby2h0mjBZwP2wpJ45zqW5JOeu

MFOFTh5GcCY90W3c3KbDVNCWeVLW1JsQ_8a2evANoJRN2mkYXZibZ0bzIuna. - https://www.fda.gov/media/136939/download.

- https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cdrh-strategic-priorities-and-updates/cdrh-seeks-public-comment-increasing-patient-access-home-use-medical-technologies.

- https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cdrh-strategic-priorities-and-updates/cdrh-seeks-public-comment-increasing-patient-access-home-use-medical-technologies.

- See https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/cdrh-strategic-priorities-and-updates/cdrh-seeks-public-comment-increasing-patient-access-home-use-medical-technologies. See also CDRH Strategic Priorities, available at https://www.fda.gov/media/155888/download.